Editor's Note

We are gearing up here at the Consortium for the Futures

of Entertainment conference, which is now less than two weeks

away. If any of you within the Consortium who are coming to Cambridge

for the event next week have any questions about what to do while you

are here, or interest in connecting with other folks involved in the

Consortium while you are here, feel free to be in touch.

This week's newsletter features an Opening Note

from the Consortium's research manager, Joshua Green, who

provides

an advanced copy for a piece he is writing for FlowTV, the online critical forum on

television and media culture from the University of Texas-Austin's Department of Radio,

Television, and Film. This piece, based on work

that Joshua has been doing on how to brand a television network in a

cross-platform media environment, is the first in a series of pieces he

is writing for Flow. He plans to include the three following

installments in this series in future issues of the C3 Weekly Update.

Eleanor Baird's series on valuing fan

communities

returns this week in the Closing Note with the fourth installment.

Eleanor, who is one of our research assistants here in the Consortium

and a graduate student at MIT's Sloan

School of Management, will

provide the final installment in next week's Closing Note. For those

who missed the first three pieces in this series and do not have the

copies archived, feel free to contact me for a PDF version. This week's

newsletter has come out a little later

than usual to help facilitate a longer-than-usual Closing Note, but we

are excited about this series and hope that

it is of use to many of you readers.

As usual, the newsletter this week features all

the entries published during the week on the Convergence Culture

Consortium Weblog.

Also, please let me know as usual if you are having any trouble

receiving the

newsletter. If you have any questions or comments or would like to

request prior issues of the update, direct them to Sam Ford, Editor of

the Weekly Update, at samford@mit.edu.

|

|

In This Issue

Editor's Note

Opening Note: Joshua Green on the Branding of

Television Networks

Glancing at the C3

Blog

Closing Note: Eleanor Baird on Valuing Fans, IV of

V: Working It Out: The Model Fan?

|

Opening Note

What Does an American Television

Network Look Like?

As U.S. networks adjust to the shifting paradigms of

control that govern the space in which television is produced,

distributed, and consumed, the nature of the television network is

being re-written. The industry focus on 'engagement' across platforms

requires a re-imagining of what a television network looks like, how it

behaves, and how it constructs its audience. Though not completely dead

yet, the network ident, historically crucial to the construction of

network identity, has been stretched by these new conditions.

Network idents themselves seem to have been absent from

U.S. television for a while now. Though the network's featured promos

for the fall line-up advertises the highlights of the coming season,

ongoing promotional material selling the network itself is, in the

words of ABC marketing chief Michael Benson,

"fairly low on the totem

pole." (McPherson 2006).

Indeed, ABC's

Yellow "I Like TV" campaign of the 1990s

is still popularly remembered as the last network-wide branding

campaign that had any real impact (Friedman 2007), and the current

emphasis seems to be on promoting programs as sub-brands rather than

focussing on network "cheer" (McPherson 2006). This approach resonates

with current discussions about the changing nature of television's

form, particularly the decoupling of television programming from the

television schedule and advertising modes (Carlson 2006), and the

increasing disconnect between content and the broadcast medium (Dawson

2007; Hills 2007; Kompare 2006).

The absence of overarching branding campaigns

articulating the nature of the television network - advertising,

consequently, it's appeal to audiences - raises a question, however,

about what a television network looks like in the current climate.

Television branding, Benson told Broadcasting and Cable in

2003, "is not simply graphic packaging; it is developing a voice,

personality and feel for a network and its programming." ("Brand

Builders", Broadcasting and Cable June 2, 2003). Reflecting on

his time at VH1 in the 1980s, Benson remarked, "It dawned on me that we

needed to take more of a packaged-goods approach to branding

[television] - to create our 'Coke can' or 'Cheerios box,' - and then

prove to our audiences who and what VH1 was about." ("Brand Builders", Broadcasting

and Cable June 2, 2003).

While a little blunt, the 'packaged-goods' metaphor

seems a useful one to describe some of the work television idents have

traditionally played. In the U.S. cable market, this description would

still seem apt (consider USA's "Characters Welcome" or Bravo's "Watch

What Happens" campaigns), and, though it doesn't account for the

community-forming role idents play, it would also seem to describe, to

some extent, the role of ident campaigns in places such as the U.K. and

Australia.

U.S. networks, however, have progressively eschewed this

model of television branding, moving further towards program-specific

promotion at the expense of network identity campaigns. The germ of

this movement might be traced to the watermarking of content in the

early 1990s in response to the increased mobility of viewers in a

multi-channel environment. ABC introduced watermarks as part of their

1993 attempt to position the network as a 'superbrand' (Mandese 1993),

promoting programs rather than the season's lineup and marking their

programming with the now standard visual reminder of the content's

origin to make apparent the link between program and network.

The emphasis on program brands as opposed to network

identity makes a certain degree of sense given the declining role of

the schedule as a way to structure audience engagement, increasing

personalization of both content streams and sites of consumption

(Carlson 2006; Dawson 2007), and move further toward

first-order-commodity relationships with viewers (Hills 2007; Johnson

2007). And yet, the Networks have not fully transitioned to a status as

program producers or content providers. The organizational form of

television still relies on individual programs contributing to the

cumulative success of the network, meaning there may still be some

value in promoting the network brand. This brand, however, is one that

now stretches across not only multiple content types but also multiple

sites of consumption or engagement, and this requires a shift in the

way the network is constructed through ident materials.

Despite the current elusiveness of network identity

material on American television, ABC's "Start Here" provides an insight

into the way US Networks are adjusting to the challenges of

representing the network in the current market. Rolled out with their

Fall 2007 line-up, "Start Here" presents ABC as the launching point for

engaging with their content regardless of platform. Built around a

graphics package featuring revolving icons representing a TV, computer,

iPod, and cell phone, it features a prominent "play button" on the

flip-side of the ABC medallion and a reminder to viewers the Network is

the official source for accessing content.

Expressly offering viewers the promise of content

available "anytime, anywhere", the campaign attempts to establish the

significance of the Network in an era of textual and viewer mobility.

As Dawson (2007) argues, 'mobility' as it pertains to the current

television moment needs to refer not only to the physical mobility of

viewers but also to the mobility of television texts, available and

portable across platforms. Having traditionally only made limited

offerings available through official or sanctioned sites, the Networks

are yet to ascend to a status as the predominant sites beyond

television viewers can access content through.

ABC's approach, then, attempts to establish the network

not only as the party responsible for the production of content, but

also as the site responsible for the distribution of this content

across platforms. This campaign represents a determined shift away from

network branding strategies of old which positioned the Networks as

sources for the experience of television. Consider, for instance, NBC's

"Come

Home to NBC" or "Be There"

campaigns from the 1980s where the network was actively constructed as

not only domestic but the site itself through which the television

experience took place.

If anything, "Start Here" serves to drive viewers away

from the television set, responding to the fact the consumption of

television content is no longer medium or temporally specific. Similar

tendencies are present in the break bumpers NBC uses during commercial

pods to remind viewers they can consume more - additional content,

encores, two-minute recaps and the like - over at NBC.com. These break

bumpers play with the feathers of the NBC peacock, using one feather

each spot as a substitute for a mouse pointer while the content

available online is promoted (a similar strategy is employed by NBCU

owned cable channel Bravo).

What is significant about ABC's campaign, however,

particularly in comparison to NBC's break bumpers, is the way it

constructs the television network itself as a multi-platform object.

"Start Here" portrays ABC as a network that exists across multiple

platforms, rather than emphasizing (as NBC does) that the television

experience is supported by extra-medium materials. Referring to ABC in

the first person (suggesting viewers "start with us") and presenting

the platforms as virtually equivalent or interchangeable as sites for

consumption (which in practice is untrue), the campaign re-imagines the

television network as a network oriented around television content,

rather than one organized around the television medium or the shared

experience of consumption.

Works Cited

Carlson, Matt. (2006) "Tapping into TiVo: Digital video

recorders and the transition from schedules to surveillance in

television," New Media & Society, 8 (1): 97-114

Dawson, Max. (2007) "Little Player, Big Shows: Format,

narration, and style on televisions' new smaller screens," Convergence,

13(3): 231-250.

Friedman, Wayne. "Peacock

Ruffles Feathers, Launches Brand Effort", Media Daily News,

07/17/2007, accessed September 17, 2007.

Hills, Matt. (2007) "From the Box in the Corner to the

Box Set on the Shelf," New Review of Film and Television Studies,

5(1): 41-60.

Johnson, Catherine. (2006) "Tele-Branding in TVIII: The

network as brand and the programme as brand," New Review of Film

and Television Studies, 5(1): 5-24.

Kompare, Derek. (2006) "Publishing Flow: DVD Box Sets

and the Reconception of Television," Television & New Media,

7: 335-360.

Mandese, J. "ABC's 'superbrand': Net powers up plan to

bolster programming", Advertising Age, 6/14/1993: 2.

McPherson, Steve. "ABC's Benson Pushes "One" Campaign," Broadcasting

and Cable, 6/12/06: 2, 24.

Joshua Green is the research

manager for the Convergence Culture Consortium and a Postdoctoral

Associate at the Comparative

Media Studies program at MIT.

Glancing at the C3 Blog

|

Jesus

2.0: Christianity in Cyberspace. In light of a recent Forbes

piece on Christianity in the Web 2.0 world, Sam Ford looks at several

of the pieces featured on the C3 blog in the past couple of years

dealing explicitly with the way Christian communities are using

technology in interesting ways, and business models built around

creating Christian media audiences and users.

The

Black Nerd: A Stereotype to Break Stereotypes? Sam Ford looks at

the recent post by Desedo Films' Raafi Rivero on the history of the

black nerd and the ways in which conflicting stereotypes help

complicate prejudice.

Bluegrass

Music and Fan Tourism at Jerusalem Ridge. Sam Ford looks at his

hometown's appearance on the front page of the Travel section in

Sunday's New York Times and how fan tourism can be a

draw for music industries like bluegrass.

The

Future of Niche Cinema. Sam Ford writes about shifting business

models for promoting films to target audiences and how outlets like

DVD, online video, and video-on-demand might help change the cost

structure of film production.

Looking

at the Panoramic View: The State of Online Video. Sam Ford recounts

a recent visit to the offices of Hill/Holliday to meet with C3 Alum

Ilya Vedrashko and VideoPlaza Founder Sorosh Tavakoli to discuss the

current state and future of a business model for online video. "It is

precisely the panoramic view that people like Ilya have that can make

this so frustrating. The industry is slow to change, and technological

infrastructure can often be even slower."

My

Afternoon with the Robot. Sam Ford recounts his recent visit

with Robert Doornick, founder and president of International Robotics,

and the robot he believes can still innovate education, therapy, and

marketing. "So what is the purpose of the robot? Is it to diffuse a

serious situation through an out-of-place gimmick? Is it to provide a

face to marketing that isn't tied up with preconceived racial/cultural

markers? Or is it to make us more aware of human nature and biases

ironically by presenting a non-human entity communicating in very

human-like ways, with a human controller? Or does it have to be any one

way?"

|

|

Looking

at the Google/Nielsen Partnership in Light of This Year's Development.

Sam Ford looks back at the Google/Echostar partnership, controversies

surrounding page counts, and second-by-second ratings, in relation to

recent news of Google further positioning itself in the television

measurement world.

MIT

Center for Future Civic Media Blog. Sam Ford writes about the

launch of MIT's Center for Future Civic Media, through a grant with the

Knight Foundation, and the breadth of coverage on their blog, spanning

not only issues in the journalism world but also posts like CMS

graduate student Abhimanyu Das' recent piece on the Comic Book Legal

Defense Fund.

A

Transformation of Our Own: Fanfiction Communities and the Organization

for Transformative Works. Xiaochang Li writes about the

Organization for Transformative Works, the new fan-run

organization which is seeking to create its own archive of fanfic as a

reaction to the FanLib controversy, which sought to create a commercial

outlet for fan fiction content.

Growing

Up in the 1930s: How Media Changes our Relations to the Past. Henry

Jenkins looks at the amount of historical television and radio content

he consumed in his youth and how the media of the past can still be

relevant to the present.

What

Value Is There in Being LinkedIn? Sam Ford takes an audit of his

own LinkedIn network and starts a discussion with readers on the worth

of maintaining a network on the site, based on a recent piece from

Peppercom's Steve Cody on whether maintaining a LinkedIn page is worth

the effort it takes.

Around

the Consortium: Gender and Fan Studies, WGA Strike Lost.

Avi D. Santo and Barbara Lucas participate in the latest round of

discussion on Henry Jenkins' blog, while The Extratextuals look at what

the writers' strike might mean for the industry and Jason Mittell

shares an upcoming publication entitled "Lost in a Great Story:

Evaluation in Narrative Television (and Television Studies."

|

Follow the Blog

Don't forget – you can always post, read, and carry out

online conversations with the C3 team at our blog.

Closing Note

Valuing Fans, IV of V: Working It

Out? The Model Fan

Comic Book Guy: Last night's Itchy & Scratchy

was,

without a doubt,

the worst episode ever. Rest assured I was on the internet within

minutes registering my disgust throughout the world.

Bart Simpson: Hey, I know it wasn't great, but what

right do you have

to complain?

CBG: As a loyal viewer, I feel they owe me.

Bart: What? They're giving you thousands of hours of

entertainment for

free. What could they possibly owe you? I mean, if anything, you owe

them.

CBG: Worst episode ever.

Source: The Simpsons Archive: Comic Book Guy File, http://www.snpp.com/guides/cbg.file.html

After a short hiatus, we return to the questions raised

two weeks ago in my previous installments of this thought piece on

beginning to

quantify fan engagement based on previous qualitative work that C3 has

done on categorizing fan behaviors.

In this installment, I will revisit our index from last

time, and

discuss in more depth what it might mean and how we might use it to

understand the potential value of fan engagement.

Back To the Index -- Feedback and More Analysis

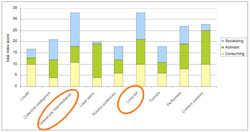

To recap, the chart is a visual representation of

different forms of fan behavior and engagement, based on criteria for

loyalty set out in the marketing literature, and the three behavioral

categories: socializing, activism and consuming. The bars represent the

total index points that each role received in the analysis (to a

maximum was 45), and the colored sections the proportion of the points

that came from each of the three behavioral categories (with a maximum

of 15 points each).

Based on input from my colleagues at C3, I changed the

order of engaged behaviors in the "consuming" section. The updated

chart appears above and the table on the final page of this document.

The objective of this exercise was to enable us to

visualize and scale the proportion of activity within each role, or

type of fan behavior, that is related to consuming, activism and

socializing. It is important to note that this is about fan engagement

with a media property, not with the advertising, which will be

addressed in a future piece.

Observations

From this exercise, we see that although loyals,

grassroots intermediaries, long tail fans, and content creators all

have similar levels of consumption under the index, the loyals, the

group of fans identified in C3's research as the traditionally most

valuable given the current economics of the television industry are

actually not the most engaged. For the time being, I will focus on that

finding and come back to the other points later.

The Big Ideas

What are the implications of this? If indeed the

"grassroots intermediary" and "lead user" behaviors represent the

highest levels of engagement, it suggests that true engagement with the

program is not about that first broadcast airing, or success of a

product when it is launched, but what happens to that property and its

fan base over a longer period of time.

Consequently, the value of these engaged audience

members is not just difficult to quantify, but is complicated by

realization over a long period of time. So, is measuring engagement the

best way of establishing ad rates or reaching of the appropriate

demographic targets? I would argue that it is not.

Ideally, if you are in agreement with this chart, a fan

who is a grassroots intermediary and a long tail user, perhaps someone

who watches a show after (and also perhaps during) the initial network

run and promotes it to others. And therein lies the key -- the value of

an engaged audience may not lie so much in what they do to interact

with the property in any way, but how they create conditions for others

to do so.

So, the question then becomes, what is the value of this

long-term audience, and is it more or less than the eyeballs on the

screen at the time of airing or, as the industry seems to accept, three

days later?

Assessing Long-Term Value

This installment and part five focus on answering this

very question. As always, my first step was to look at literature in

various disciplines to see if there were any tested models that could

be applied. The difficulty here is always knowing exactly the extent to

which how these models are transferable.

Marketing research and models are helpful, but present

interesting problems.

There is a fair amount of literature dedicated to

consumer lifetime value (CLV), how to calculate it, and how much it

should factor into the company's marketing decisions. There has also

been a fair bit of work done on and customer relationship management

(CRM) the value and motivation of word-of-mouth.

CLV is a particularly interesting concept to examine

here, because no matter how you calculate it, the basic premise is that

it is seeking to find the present value of all future monetary

transactions that a company has with a particular type of customer,

less the promotional and usually acquisition cost of those revenue

streams. Like the model I am attempting to create here for audiences,

CLV models generally seek to understand groups of customers, not

individuals. The models can get very complex, but the key variables

seem to fall into four categories:

Scale: Number and type of distinct

customer groups.

Behavior: Probability of repeat

purchase, propensity for cross-buying/picking up similar products,

variation in customer activity in each cycle (season), word of mouth

activity

Retention & Acquisition: Overall

retention and acquisition rates, trial rate relative to regular

consumption, switching costs to the consumer, customer communication

and involvement (with the corporation).

Cost & Revenue: Advertising

expenses, discount rate, consumption rate, transaction size and

contribution margin

Some of these variables do apply to fans, but as the next section will

explain, some are not closely related to the fan behaviors that we have

been looking at.

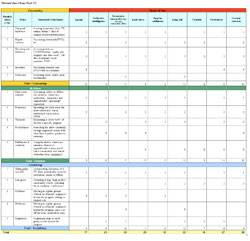

My first step was to create a table of the fan behaviors

we have been working with and compare it against the preceedng

variables from CLV models to determine what characteristics the ideal

model would focus on to value engaged fans.

Currency Conundrum

To use any of the models, we would need to work out is

what the currency in valuing fans could be. In the absence of

advertising revenue as a currency, there are three potential units of

measurement, which I see as playing, generally speaking, into the forms

of fan engagement that the "Fanning the Flames" study outlined as shown

in the table below.

Not surprisingly, the consumption category generally

requires money, while the other two require relatively large amounts of

time and what I have called "affinity," meaning a strong emotional

investment in the property and a desire to publicize it in order to see

it continue.

To visualize how these currencies might relate to

existing metrics, in the columns next to those, I have put in the CLV

metric(s) that seemed to be the best fit.

Organizing my thoughts this way, a couple of things, not

altogether surprising, stood out:

The "most engaged" behaviors involve some of all three

currencies, but a significant time investment is the most common element

Currencies for measurement pose a real problem, but

relative rates may be a workable measure over a dollar value

Time, which can be assigned a dollar value, but a

single rate is tough to pin down, whereas time in itself is quantifiable

Affinity, the second most common potential currency is

extremely problematic to assign a monetary value to, but ranking

relative to other media properties may be an option

Money, outside of the consumption category, is not a

very common factor

Retention/repeat patronage seems to be the element that

relates most in all of these behaviors to potential CLV metrics

WOM, although not easy to quantify, may also be a

useable metric

Estimated repeat purchase of media property-related

items may also be useable to measure fan behavior

I also began to think about how the ad-supported model

figures into this – in other words, could we value these different

types of fans based on viewing ads, in the traditional publishing-style

model. I have more or less come to the conclusion that that may be

possible, but it would require data that’s really beyond the scope of

this piece, but that is probably also not practical to obtain and

segment as an activity separate from assessing overall viewership.

So, it appears that a lot of the CLV metrics that many

of the models use are, not surprisingly, a bit difficult to use,

primarily because conversion to a single currency is problematic.

Before my next installment, I will try to find a metric or model in the

literature that only uses the stronger elements, but my sense is that

there is not a single one at the moment that will fit appropriately. A

metric for fan engagement will probably need to be made up of a number

of elements, combined in a way that makes sense in the context of the

environment in which they operate. Public relations metrics may

actually prove to be a better fit than CLV.

Next time: Measuring fan impact on the rest of the

audience

Coming back to my earlier argument that a large part of

the monetary value of fans comes from recruiting and retaining others,

in my next piece, I will look at CLV for an average viewer and how time

spent and affinity among fans may have an impact on the value of those

customers. At this point, I will also bring in a discussion on

advertising and how engagement in ads, rather than content, might be

integrated into this discussion.

See below for a revised chart from Part III.

Until next time…

Part of the intent of this series is to encourage

discussion of what I am attempting to do here, why, and how it might be

a useful tool for industry. If any reader has questions or comments

about the methods or data used here, please email me at ecbaird@mit.edu.

Beck, Jonathan. "The sales effect of word of mouth: a

model for creative goods and estimates for novels." Journal of

Cultural Economics. January 2007, Vol 35, p5-23.

Berger, Paul D. ; Nasr, Nada I. "Customer lifetime

value: Marketing models and applications." Journal of Interactive

Marketing. March 1999, Vol. 12, Issue 1, p17 - 30.

Berger, Paul D.; Weinberg, Bruce; Hanna, Richard C.

"Customer lifetime value determination and strategic implications for a

cruise-ship company." Journal of Database Marketing & Customer

Strategy Management; September 2003, Vol. 11 Issue 1, p40-52.

Dodson, Jr., Joe A; Muller, Eitan. "Models of New

Product Diffusion Through Advertising and Word-of-Mouth". Management

Science. November 1978, Vol. 24, No. 15, p. 1568-1578.

Eleanor Baird is an MBA

Candidate, Class of 2008, at the MIT Sloan

School of Management. She has worked as a Research Assistant with the

Convergence Culture Consortium since February 2007. Email her at ecbaird@mit.edu.

|