The Japanese popular culture industry, especially for anime and manga, is an interesting case study for global fandom, but also for global industry. The comics, television, and film industry for animated popular culture in Japan has its own history, structure, and approaches, but over the past five decades, as it has reached millions of new, international viewers, new industries have risen to cater to these fans. Still, with the rise of the Internet and the economic troubles that most industries have gone through over the past decade, both the domestic and international manga and anime industries have been hurting for money, even with a surfeit of fans.

The anime and manga industry is especially volatile, because its domestic and international audiences have utilized the Internet to spread and consume the media at the expense of industrial and commercial models that cannot keep up with the audiences' changing tastes, modes of consumption, and cultural behaviors of media consumption (sharing with friends, international online distribution, the culture of collectors versus mere viewers, etc.). The industries, both in Japan and elsewhere, must change: however, the success that anime and manga brought a decade ago have influenced the producers of these media to stick with old models that are no longer fully applicable to the current fan cultures that drive the markets.

Today, I want to discuss two very recent issues of the manga and anime industries -- in Japan and in America -- publicizing comments to fans in a way that might be seen by many as "giving up": without adapting to technological, cultural, and commercial changes, the industries representatives have voiced concerns to fans by pleading with them to stop behaving as they current are -- mostly by using the Internet to circumvent commercial models for their media consumption -- and to think ethically about how these behaviors are affecting the respective industries.

More after the jump.

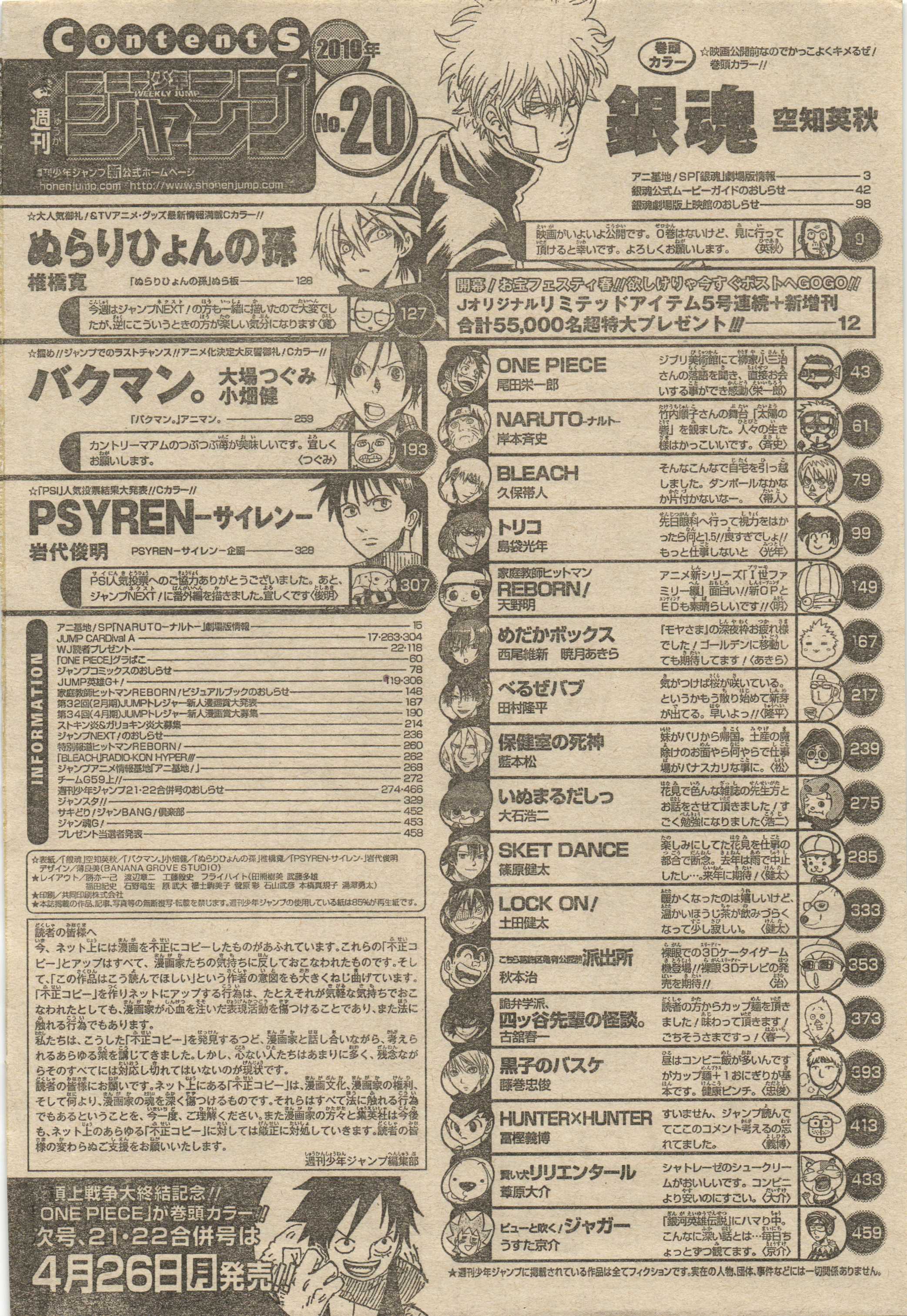

Shueisha, a major publisher in Japan who print manga magazines and also co-own Viz (one of the top manga publishers in the United States), last week printed a letter to fans in Weekly Shonen Jump, a weekly manga magazine and one of the most popular in Japan. You can see the message (in the original Japanese) by clicking on the image below (in the bottom right), or read the translation:

To all our readers,There are now many people unjustly posting copies of manga on the internet. These unjust copies are inconsistent with mangakas' feelings. They are also distorting the authors' intentions of "I want the work to be read this way". The actions of posting these unjust copies on the net, into which the mangakas have poured their hearts, are not only hurting mangakas in real life but are also against the law, even if done in a light-hearted manner. Every time we discover such "unjust copies", we talk to the mangaka and consider every possible countermeasure. But the number of inconsiderate people is great, and at present we cannot deal with all of them. We have a request for all our readers. The unjust internet copies are deeply hurting the manga culture, mangakas' rights, and even mangakas' souls. Please understand once again that all of that is against the law. Also, the mangakas and Shueisha will severely deal with any unjust copies found on the internet. We ask that our readers please continue to support us.

- Weekly Shounen Jump editorial department (translation via Devang Haven)

This is a critical development in the manga industry, not because the publishers are finally making a statement about the state of fan piracy, but also that the message comes from one of THE important players in the Japanese industry.

Now, there is some context behind this message: although here in America, a lot of talk goes around about the negative impact of scanlations (scanned and translated manga, by fans), this message is calling out specifically to a Japanese audience: fans in Japan who are uploading RAW scans of manga magazine pages to the Internet (that is, scans of the original pages: a direct copy of the book, circulated online away from the commercial market).

Now, the uploading of RAW scans in Japan is an obvious act of piracy, and direct piracy like this does hurt the industry. An interview with Ed Chavez (Vertical, Inc., a publisher of translated manga in America) explicates that copying of the primary source affects sales and loses audience members. And in response to Shueisha's plea, a number of websites that hosted RAW manga are now closed or redirect to Shueisha's homepage.

The issue with a message to Japanese fans is how international audiences should react to this call for fan ethics. A number of English-language sites carry RAW manga scans, for fan translators to distribute scanlations to English-speaking audiences. Although these scanlations still affect the market, they are not scans of the official translations published by companies in North America: therefore, they occupy a slightly different space. If we think philosophically about scanlations, then, English-language-only scans of manga available in Japan but not yet in America operate in a strange space: they can't be read by Japanese fans who are looking for free Japanese-language manga, but they help spread the word about titles not currently available in English-speaking countries (at the same time, though, the consumption of scanlations may still affect the purchasing of these official copies once they are released, because some fans will have already read the scans and will not want to buy the official publication).

Will Shueisha's plea work? Sales of manga in Japan have been on a steady decline for a few years now, due in part to piracy, but also to new modes of media consumption, for example through cell phones. All in all, it appears that the most important part of this issue is that Shueisha, as a major publisher, has the capacity to send cease-and-desist notices to websites that are sharing their original content for free (an illegal activity). These endeavors may help the Japanese industry's woes with declining sales, but I would venture a guess that it will not affect overseas fan economies.

If we jump across the Pacific to America, another rhetorical development took place, this time via a message published by the president of an imported Japanese animation production studio.

Anime News Network reports:

Eric P. Sherman, President and CEO of the anime dubbing company Bang Zoom! Entertainment, has posted an editorial on the AnimeTV blog on Saturday, urging fans to buy anime instead of watching it via fan-subbed videos.

Bang Zoom! is a North American distributor (voice dubbing, subtitling, production, etc.) of Japanese animation television series, movies, and the like. Sherman, in his blog post entitled "Anime - R.I.P.," writes in bold, "Anime is going to die." He reiterates what many critics have been saying for years -- "If people don't resist the urge to get their fix illegally, the entire industry is about to fizzle out." -- but readers, both fans and those in the industry, realize that his words are about a decade too late.

The issue, of course, is that Sherman argues, "Japan is already suffering and struggling to bring out quality titles. They can't rely on everything being picked up by US distributors anymore." The problem with his argument is two-fold: 1) the Japanese domestic market is the key contributor to the financial success of Japanese animation, not a reliance on foreign distributors, and 2) the Japanese domestic market has been deteriorating as much as the redistribution market abroad (Adrian Brown, of SBS Dateline Australia gives a good rundown of the Japanese industry's problems in this video segment).

In terms of American redistribution, FUNimation Entertainment currently leads the market in DVD releases (both dubbed and subbed), with Crunchyroll picking up the majority of what titles are left, releasing them subtitled online in their video portal. However, to repeat, the American licensors only provide a reasonable (though still small) fee to Japanese companies to distribution their intellectual property. Basically, the Japanese producers are taking what money they can get (especially money they can use to make up for domestic piracy losses), instead of letting reasonably accessible money slip by while foreign fans share subtitled anime online. Justin Sevakis, of Anime News Network, breaks down the process below:

The cost of producing TV anime has tripled in the last decade. The Japanese DVD market is also maturing, and R1 imports back into Japan for a third of the price (or less) of R2 are a growing problem for them. Hence, if they're going to part with their intellectual property, it has to be worth at least the amount they're likely to lose in reverse-imports, plus the production burden relative to whatever value they've attached to the R1 market in relation to the rest of the world.When an anime is licensed, is the fee paid to the Japanese companies in the form of a one-time XX dollar payment, or in the form of XX dollars or XX percent profit off of each DVD that is sold?

Sort of a combination of both. Let me preface this by saying that the following isn't just how anime works, but pretty much every motion picture and TV license.

First, there is an up-front change of money, known as the "license fee" or "minimum guarantee". In the case of TV or OAV, this is usually a per-episode amount (though a licensor may insist on dividing longer series up in specified chunks of episodes). There's also likely a charge for materials duplication (as cloning master tapes is expensive).

The releasing company then produces whatever DVD product and sells it (and may also have other rights like theatrical, TV, etc...). A certain percentage of those grosses are separated into a separate fund. That fund is used for the following:

1. Recouping any production costs. This includes dubbing, DVD authoring, replication and manufacturing, etc...

Once that's all recouped, THEN...

2. Recouping the minimum guarantee. As the "minimum guarantee" implies that this is the guaranteed amount of revenue the licensor will make from the deal, funds are withheld until that amount is actually reached.

AFTER THAT POINT...

3. That percentage is paid as royalties to the licensor.Now, that's a lot of money to make back before the licensor sees any residuals. You're probably wondering how many titles actually result in residuals being paid, and the answer is "not many". The minimum guarantee is there so that even if the release tanks, the licensor will have made enough money to call it a day, but OTOH won't lose out if it's an unexpected success. Likewise, since the label takes the majority of the risk, they get to keep the lion's share of the profits, should the release do well.

This is how the vast majority of deals are structured, and this system has been around in the entertainment industry for as long as anyone can remember. There are some exceptions, and the minimum guarantee and back-end percentages ("points") vary substantially. Also, sometimes production expenses are recouped before separation into royalty percentages.

Justin Sevakis, Anime News Network (via ANN Forums)

All in all, the ultimate problem facing American distributors is that the cultural modes of anime consumption in America is changing once again: instead of needing a general and mediated flow of access to Japanese animation (which was achieved via voice-dubbed distribution), fans now want 1) immediate access to content to keep up with fellow fans, with whom they discuss shows online regularly and at a quick pace; and 2) subtitled anime, because hardcore fans have lashed out about authenticity of dubbed productions, through which many American redistribution directors have taken upon themselves to "redirect" in terms of voice acting (ie., it is a novel production, recontextualized for foreign fans). Instead of needing a moderator to introduce Japanese cultural concepts, terms, etc., most contemporary fans understand (at least the basics) of Japanese lifestyles, language, and behavior.

Therefore, it seems to me that Sherman's plea for fans to "not pirate anime" is moot, at least at the end of this decade. He states, "Do the right thing. Plain and simple. Because if you don't, I can guarantee you that this time next year, Bang Zoom won't be bringing you anymore English language versions of it." However, it seems that in relation to American fans' modes of consuming anime, English-language dubs are no longer necessary. Instead, the model provided by Crunchyroll -- immediate licensing of popular series, subtitled, and only set to stream online -- caters to the largest general American anime audience. Dubbed anime in America might slowly fizzle out, but that business model will be replaced by another company that can better respond to fans' behaviors.